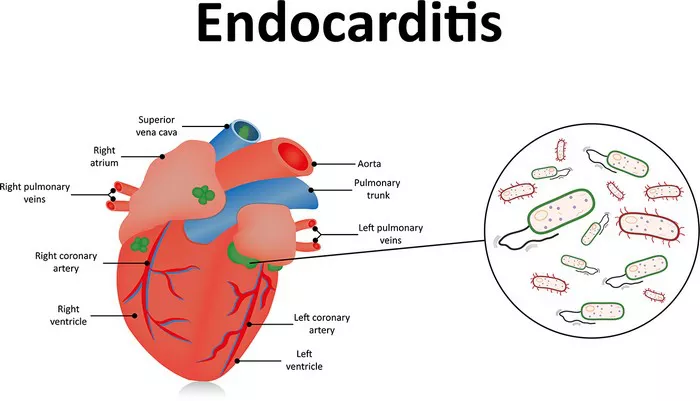

Endocarditis is a serious, potentially life-threatening infection characterized by inflammation of the endocardium, the inner lining of the heart’s chambers and valves. This condition primarily results from microorganisms, predominantly bacteria, entering the bloodstream and attaching to damaged areas within the heart. Understanding the detailed aspects of endocarditis—including its causes, symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options—is crucial for early diagnosis and effective management.

Causes of Endocarditis

Endocarditis is most commonly caused by bacterial infections, although fungi and other microorganisms can also be responsible. The pathogenesis involves microorganisms entering the bloodstream (bacteremia) and adhering to abnormal or damaged heart tissue, particularly the valves. The primary sources and risk factors facilitating this process include:

Bacterial Entry via Medical Procedures: Dental procedures that involve gum cutting or invasive dental work can introduce bacteria into the bloodstream, especially if oral hygiene is poor. Similarly, surgeries, catheterizations, or other invasive procedures can serve as entry points.

Poor Oral Hygiene and Dental Infections: Bacteria from the mouth, such as Streptococcus viridans, can enter the bloodstream during routine activities like flossing or brushing if gums are inflamed or infected.

Intravenous Drug Use: The use of contaminated needles introduces bacteria directly into the bloodstream, significantly increasing the risk of endocarditis, especially with skin flora like Staphylococcus aureus.

Preexisting Heart Conditions: Congenital heart defects, damaged or prosthetic heart valves, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or previous episodes of endocarditis create environments conducive to microorganism adherence and colonization.

Medical Devices and Prosthetics: Artificial heart valves, pacemakers, or other implanted devices can serve as surfaces for bacterial attachment.

Other Factors: Long-term indwelling catheters, immunosuppression, and certain chronic illnesses like diabetes or kidney disease also predispose individuals to endocarditis.

Symptoms of Endocarditis

The clinical presentation of endocarditis varies depending on the causative microorganism, the extent of infection, and the patient’s underlying health. Symptoms may develop gradually or suddenly, often mimicking other illnesses such as influenza, which can delay diagnosis.

Common Symptoms

Fever and Chills: Persistent high temperature is one of the hallmark signs.

Fatigue and Weakness: Due to systemic infection and impaired cardiac function.

Muscle and Joint Aches: Aching joints and muscles are frequent, reflecting systemic inflammation.

Night Sweats: Often accompanying fever.

Shortness of Breath: Due to heart failure or pulmonary embolism.

Chest Pain: Especially when breathing, indicating pleural involvement or pericardial irritation.

Swelling: Edema in the feet, legs, or abdomen due to heart failure.

New or Changed Heart Murmur: Abnormal sounds caused by turbulent blood flow from valve damage.

Less Common Symptoms

Unexplained Weight Loss: A sign of chronic infection.

Blood in Urine (Hematuria): Due to embolic phenomena.

Splenic Tenderness: From embolic infarcts.

Janeway Lesions: Painless, flat, red or purple spots on palms or soles.

Osler Nodes: Painful red or purple bumps on fingers or toes.

Petechiae: Tiny purple or red spots on skin, mucous membranes, or eyes.

Systemic Manifestations

Patients may also experience general malaise, anorexia, and night sweats, reflecting systemic inflammatory response. The variability in symptoms necessitates a high index of suspicion, especially in at-risk populations.

Risk Factors for Endocarditis

The likelihood of developing endocarditis increases with specific predisposing factors:

Age: Most common in adults over 60 years.

Prosthetic Heart Valves: Artificial valves are more susceptible to bacterial colonization.

Damaged or Congenital Heart Valves: Conditions like rheumatic fever or congenital defects increase vulnerability.

History of Endocarditis: Recurrence risk is elevated.

Intravenous Drug Use: Introduces bacteria directly into circulation.

Poor Dental Hygiene: Facilitates oral bacterial entry.

Medical Devices: Pacemakers, catheters, and other implants.

Immunosuppression: Conditions or therapies that weaken immune defenses.

Diagnosis of Endocarditis

Early diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical suspicion, blood tests, and imaging:

Blood Cultures: Essential for identifying causative organisms; multiple samples improve accuracy.

Echocardiography: Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) provides detailed visualization of vegetations, abscesses, or valve destruction.

Laboratory Tests: Elevated inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP), anemia, and leukocytosis.

Other Tests: Roth spots, petechiae, or splenic infarcts may be observed during physical examination.

Treatment of Endocarditis

Effective management involves prolonged antibiotic therapy, and in some cases, surgical intervention to repair or replace damaged valves.

Antibiotic Therapy

Empirical Treatment: Initiated promptly with high-dose intravenous antibiotics targeting common pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridans.

Targeted Therapy: Adjusted based on blood culture results; duration typically ranges from 4 to 6 weeks.

Antifungal Treatment: For fungal endocarditis, antifungal agents like amphotericin B or echinocandins are used, often requiring lifelong suppressive therapy.

Surgical Intervention

Indicated in cases of:

Severe valvular destruction causing heart failure.

Persistent infection despite antibiotics.

Large vegetations at risk of embolization.

Abscess formation or fistula development.

Prosthetic valve endocarditis requiring removal or replacement.

Common procedures include valve repair or replacement with mechanical or biologic prostheses.

Supportive Care and Monitoring

Patients require close monitoring during therapy, including regular blood cultures to assess treatment efficacy and echocardiography to evaluate cardiac function. Management of complications such as heart failure, embolic events, or arrhythmias is integral to care.

Conclusion

Endocarditis remains a complex and serious condition requiring early recognition and comprehensive management.

Understanding its causes, recognizing the diverse symptoms, and adhering to appropriate treatment protocols significantly improve patient outcomes. As advances in medical care increase the number of individuals with prosthetic valves and cardiac devices, awareness and preventive measures become ever more critical in reducing the burden of this potentially fatal disease.

Related topics: